Geneva, March 2020, summary by Jéssica Ayala Tejedor, Josh Goldsmith, Sébastien Longhurst

Following November’s remote interpreting workshop in Bern, AIIC Switzerland hosted a Seminar on Remote Interpreting in Geneva on February 29, 2020.

The seminar featured Klaus Ziegler, coordinator of the AIIC Technical and Health Committee, Professor Kilian Seeber, Director of the Interpreting Department at the University of Geneva, Amy Brady, staff interpreter at the United Nations Office at Geneva, and Monica Varela Garcia, Chief Interpreter at the International Labour Organization.

Introduction

AIIC Switzerland AB Representative Rawdha Cammoun kicked off the seminar, welcoming participants from across Switzerland as well as guests from Spain, Belgium, England, Italy, and Puerto Rico.

She thanked participants for their interest and the high turnout and noted that the session focused on the technical, research, and practical sides of distance interpreting.

She also encouraged participants to share thoughts on Twitter. (Special thanks to AIIC Belgium colleague Alexander Drechsel for his recap.)

Latest developments in RSI – Klaus Ziegler

AIIC Technical and Health Committee Coordinator Klaus Ziegler guided the morning session, which discussed remote interpreting setups, ISO standards, AIIC’s work on distance interpreting, Remote Simultaneous Interpreting (RSI) market trends, and the future of remote and onsite interpreting.

Definitions and remote interpreting setups

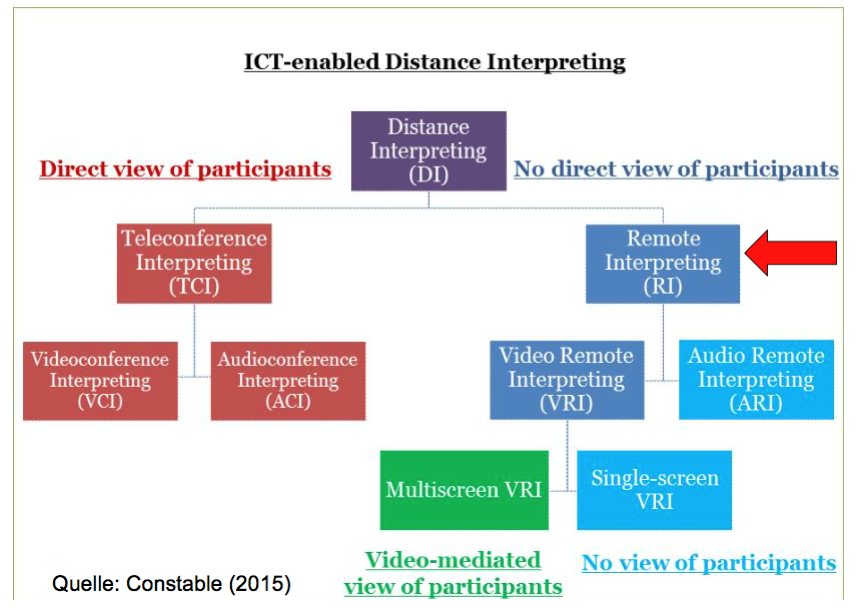

AIIC defines distance interpreting as including both teleconference interpreting and remote interpreting. The difference lies in where the interpreter is located: if the interpreter is at the venue and has a direct view of participants, but one or more speakers connect from elsewhere, this is “teleconference interpreting.” As soon as interpreters receive visual input via screens – even if they are onsite, such as in the room next door – this is “remote interpreting.” (See figure below.)

According to ISO Standard 20108, distance interpreting is defined as “interpreting of a speaker in a different location from that of the interpreter, enabled by information and communications technology (ICT).”

Digital systems allow for different setups, from the home office to the interpreting hub to the room next door. All stakeholders – including clients, technical providers, consultant interpreters, and interpreters – need to decide in advance which setup best suits the event and their communication needs (one-way communication vs. dialogue).

In the “gold standard” setup pioneered by the European Commission, interpreters work in another Commission building across the street from the conference venue, work shorter shifts, and see four different views of the conference room on their screens. On the private market, interpreters are more likely to be in the room next door. In both cases, interpreters are not in the conference room due to space limitations or aesthetic preferences. In the latter setup, interpreters usually work with a traditional hardware console and two screens showing a video feed of the speaker and the speaker’s presentation. According to Klaus Ziegler, several visual inputs may be difficult for interpreters to handle.

The home office setup is not yet addressed by ISO standards, which instead refer to the “work environment.” Home office setups are widely used in consecutive contexts in fields such as medical interpreting due to geographical constraints and language combinations. In such cases, the interpreter often selects their own equipment and responsibility shifts from the provider to the interpreter, who is unlikely to have an expensive business-quality internet connection, but may hold some responsibility – or even liability – for technical details despite having limited control over the technical environment.

At the moment, most interpreting hubs adopt hybrid solutions, combining “legacy” consoles with cloud-based solutions for transmission and distribution. Remote interpreting companies tend to market these as “software as a service” (SaaS) options which do not require hardware consoles, and which may even run on mobile devices. ISO standards have yet to consider studio or hub settings in more detail.

Whatever the setup, three main factors influence audio quality. First, the equipment used by the speaker needs to offer a wide enough frequency band. Second, codecs used by platforms can modify signals significantly, cutting out certain frequencies when compressing audio. Finally, the interpreter’s personal devices and peripherals, including headphones and sound card, also affect audio quality. Interpreters may not necessarily have control over all of these factors, yet every part of the communicative event needs to be monitored for successful remote interpreting.

If using your own equipment for remote interpreting assignments, your device needs to have sufficient resources (available processing capacity). Bear in mind that you are granting the technical provider access to your equipment.

ISO Standards

Six different ISO standards are relevant for simultaneous interpreting and conference systems. An AIIC Technical and Health Committee article describes standards 2603 (permanent booths), 4043 (mobile booths), 20109 (simultaneous interpreting equipment), and 20108 (sound and image quality and transmission for simultaneous interpreting). ISO Standard 22259, released in 2019, discusses conference systems.

ISO PAS (Publicly Available Specification) 24019 is the first standard to address “simultaneous interpreting delivery platforms.” Published in January 2020, it discusses settings where the interpreters may or may not be in the same room as participants and speakers where these platforms are used. In conjunction with ISO Standard 20108, this document includes prerequisites for the quality and transmission of sound and image to and from interpreters and includes recommendations on configuring the interpreter’s working environment.

A Publicly Available Specification aims to provide recommendations for technologies where there is a market need and limited evidence base. ISO PAS 24019 is already been used by remote interpreting providers as the reference for this field, and is also already being reviewed. The full version of ISO Standard 24019 is expected to be published in early 2021.

In 2019, the AIIC Technical and Health Committee conducted a technical study on the transmission of sound and image through cloud-based systems for remote simultaneous interpreting. The study measured frequency response, lip synchronicity, latency, intelligibility, hearing protection and audio and video quality in six different RSI platforms. It concluded that no platforms were fully compliant with the relevant ISO standards. Since then, some platforms have continued to move toward compliance; ISO PAS 24019 is likely to have a continued positive impact. The AIIC Technical and Health Committee will continue to test RSI platforms in the upcoming months.

AIIC’s work on distance interpreting

In January 2019, the AIIC Taskforce on Distance Interpreting (TFDI) published the first version of the AIIC Guidelines for Distance Interpreting. This publicly available document is intended to be shared with clients and provide guidance to interpreters. Inter alia, it recommends that boothmates be in the same room or space, a conference technician be present on site during the event, booth and consoles be in line with ISO standards, interpreters be briefed on technical aspects of the platform and have access to meeting documents, and that confidentiality and data protection be observed. The guidelines also provide information on video and audio feeds, image quality, lip synchronization, and latency.

“Conference interpreting and simultaneous interpreting are a team effort, and many [aspects of successful interpreting] depend on direct interaction between boothmates.”

In September 2019, a working group composed of AIIC TFDI members began drafting the AIIC Working Conditions for Distance Interpreting. A draft will be sent to the AIIC Executive Committee, and will be discussed at the Advisory Board meeting in June 2020. Thereafter, it could be brought to the next AIIC Assembly. If adopted, the requirements would be included in the AIIC Professional Standards and would become binding on all AIIC members.

Finally, AIIC Canada and the Canadian Parliament’s Translation Bureau have carried out tests of hearing protection devices to prevent acoustic shock. In July 2019, AIIC’s Advisory Board and Executive Committee tasked the Research Committee, Technical and Health Committee and Canada Region with working with Dr Philippe Fournier (Aix-Marseille University) to investigate acoustic shocks among conference interpreters. The preliminary findings of the project, released in December 2019, found that 47.1% of the 488 respondents had experienced acoustic shock in their work. The second phase of this research is underway.

In light of this risk, remote interpreting platforms should add acoustic shock protection; at least one reports that they recently did so. Interpreters should reconsider working with one headphone on their ear and one behind their ear, which may aggravate the consequences of acoustic shock. Interpreters using hearing protection devices should also ensure that the reaction time is as short as possible: ISO standards call for reaction within 100 ms for peaks above 94 DSPL, and the 500 ms to peak for the model initially recommended by the Translation Bureau would already have a serious impact on your inner ear.

Remote Simultaneous Interpreting market trends

Bring your own device (BYOD) platforms allow participants to use their own devices as interpretation receivers during an event. BYOD is on the rise and regularly used by remote interpreting providers as a marketing tool.

We are also seeing an increasing number of remote interpreting providers. Most, however, offer consecutive remote interpreting (“dialogue interpreting”). The number of platforms offering Remote Simultaneous Interpreting is growing very slowly. Instead, over the last 2-3 years, we have seen a consolidation of existing platforms, with some platforms disappearing. More and more hubs and studios are being established. Platforms are also promoting interpreting from your “home office.”

Many institutions are studying the possibility of using RSI. However, these institutions need solutions that are GDPR-compliant and respect their own internal IT guidelines.

Artificial Intelligence is now entering the RSI platform market. According to researchers, artificial intelligence is still far from comparable with human-level interpreting. Nevertheless, AI may be useful for very specific settings, and speech recognition and terminology-related technologies could benefit interpreters, serving as a complement to enhance our work. This topic will be discussed further at the AIIC United Kingdom and Ireland event on Artificial Intelligence and the Interpreter on March 21, 2020.

The coronavirus outbreak has also given a boost to RSI platforms. Providers have recently received many requests from institutions, companies and interpreters. While RSI may likely be the only way to prevent many of us – especially those working on the private market – from facing a slump, AIIC needs to adopt a strategy on RSI platforms and natural disasters. In doing so, it is important to be pragmatic, yet cautious, bearing in mind the long-term effects of today’s decisions.

“[We should not] drop the standards we have been defending for many years just to get a job today. Think about tomorrow. Everything adopted now as an emergency situation will be taken as a reference in the future.”

The future of remote and onsite interpreting: Four possible ten-year scenarios

Klaus Ziegler concluded by discussing four potential scenarios for the role of RSI in ten years’ time. These are summarized in the table below.

| Scenario | Onsite | Onsite and limited remote | Onsite and remote | Remote and limited onsite |

| Probability | none | low | high(est) | low/high (depending on region, market, global politics) |

| Consequences | Business as usual

Observe, don’t act AIIC: Keep her steady as she goes… |

Mainly business as usual

Be prepared “just in case” AIIC: Keep her steady as she drowns |

New business and working models

AIIC must adopt an adequate strategy |

New business and working models

AIIC must rethink and change its approach |

RSI: Smoke, mirrors and snake oil?- Kilian G. Seeber

The Seminar’s second talk aimed to provide research data to spark and enlighten the debate – as the provocative title shows. The academic vantage point offers a clear advantage on such a polarized issue: academics can ask questions active interpreters might often feel uncomfortable asking and see through the different agendas at play.

“I’m not saying anyone is misleading anyone, at least not on purpose, but every stakeholder in the situation comes to this with different objectives – or, to be provocative, agendas.”

Different agendas play out in the field of Remote Simultaneous Interpreting (RSI): companies want to make money, so they create a demand that they then meet. Professional associations protect the interests of their members. Academic research looks for the “truth”, assuming such a thing exists. In other words, we are all somewhat biased.

Platform providers feed the “RSI craze” by telling us RSI is just like being there: highly qualified interpreters work from anywhere in the world from their computers while clients save money on travel and overhead. Is this true? We don’t know much, but we do know a few things.

First, there are different DI modalities (see graph presented in Klaus Ziegler’s talk), defined by the interpreter’s view of the audience. However, we should not forget that this is an interpreter-centric approach that may be different for other players.

Second, we have numbers. In 2018, AIIC surveyed the evolution in the use of distance interpreting between 2016 and 2017. Among the 664 respondents, Video Remote Interpreting (VRI) was used an average of three days per year, with a slight increase from 2016 to 2017. Staff interpreters reported a 50/50 split between their institutions either “explicitly allowing this modality” or “making no mention of this modality”, while only 5% of institutions explicitly ruled it out. On the other hand, 70% of freelancers reported “always” or “often” having been informed in advance about the VRI use in their contracts (AIIC may wish to address this soon). It is worth noting that respondents in Switzerland do VRI less than in other markets: only 6 out of 66 had actually performed it in 2017.

Interpreters mostly worked from the conference venue (3 out of 4) or interpreting hubs (a third), while private locations (for example, homes) accounted for about 1 of every 5 events. Interpreters mostly worked from the same physical location as their boothmates (“colocation” – over 85%) and other teammates (65%). While around 70% “always” or “often” worked in soundproof environments, 38% reported non-soundproof environments: “perhaps a worrying fact that might be at odds with some of the recommendations that currently exist for provision of conference interpreting services” (K.G.Seeber). Respondents were generally provided one computer screen showing the speaker. While 80% worked mostly with traditional hardware consoles, 40% reported working via computer-based, “soft” consoles. “Wo-manning” strength remained the same 85% of the time, while the work day was the same or somewhat reduced, as was the availability of texts and documents.

Third, we have data about the interpreter’s experience. Three large studies have considered it. In the ITU (Moser Mercer, 1999) and European Parliament (Rosiner and Shlesinger, 2004) studies, both conducted in conference settings, self-reported fatigue was higher during VRI, while self-reported quality was lower. However, measured fatigue and quality were the same.

The industry’s reaction to these findings was quite obvious: as fatigue and quality are the same, we should just keep going! But is it really that simple? We know that simultaneous interpreting is one of the most complex language processing tasks. It relies on two pillars: an external constraint (an input signal that must be of sufficient quality and quantity) and an internal constraint (the human brain’s capacity). The external constraint has evolved thanks to better signal quality (including ISO booths, lag and lead, and synchronicity) and the internal constraint is constantly pushed back by training interpreters to deal with speed, density, technicity, terminology, and more.

Still, cognitive strain cannot be ignored. As sleep tests have shown, it kicks in without us noticing; accumulation can have exponential effects on fatigue. While we have no exact data on cognitive strain for interpreters working in RSI, reasonable doubt should probably be applied to the long-term effects of sustained RSI work.

So, all in all, is RSI good or bad? The FIFA study (Seeber et al., 2019) considered interpreters working remotely for the 2014 FIFA World Cup from a hub equipped with a one-screen mobile booth. It showed that interpreters’ (sometimes contradictory) expectations about their own business, hunches and myths, and likes and dislikes – rather than hard scientific evidence – are also very important.

While respondents were “less than satisfied with the screen location, the distance to screen and the feeling of presence and immersion”, they also would “largely accept this setup for full working days”. Although RSI was “always more tiring” and “always more difficult”, they “would do their job just as well, of course”, but “would advise strongly against it”.

On the other hand, some felt “remote is actually less stressful” because even though “seeing the public is good, having the public look at you all the time and knock at our door to ask for headsets” can generate stress. Some respondents also highlighted the importance of providing interpreters with “cocoon-like” rest areas when working in a hub setup, rather than merely a place to sit down in an adjacent room.

Lastly, interpreters worried about technical quality and lack of technical support in RSI settings, and suffered from lack of control and limited visual input (“the faces and grins”). Research shows that if the vision angle offered by the screen is too small, interpreters feel less immersed in the conference, an issue that could be addressed through panoramic imaging. These real concerns are at the heart of the working conditions AIIC is trying to shape.

A short version as well as a more comprehensive write-up of this interesting study are available online: https://aiic.net/page/8675/interpreting-from-the-sidelines/lang/1, https://benjamins.com/catalog/intp.00030.see.

In conclusion, drawing on asbestos – thought to be the best thing since sliced bread until we learned it causes cancer – Prof. Seeber’s message on RSI is one of caution: “Every so often it takes a while to see the physical effects of something billed as amazing.”

Videoconferences with interpretation at UNOG – Amy Brady

Amy Brady discussed the problems the United Nations faces with videoconferences, when interpreters are in the room but some of the speakers participate remotely. She shared the procedure adopted by the United Nations to deal with these situations. This is equally relevant for colleagues working outside the United Nations: 98 % of attendees at the 2019 meeting on RSI in Bern reported interpreting videoconferences.

In the past, UN interpreters only interpreted videos or remotely delivered speeches if a script was provided. However, the use of videos and video conferences and pressure to interpret them has increased in recent years, although quality has not improved. As a result, the UN drew upon guidelines prepared by SCIC to prepare suggestions to improve sound quality during videoconferences.

Several days before a meeting, interpreters share these guidelines with remote participants and run a sound test to assess compliance. After the test, an Assessment Report is written and sent to the team leader, who decides whether interpretation will be provided. If tests reveal poor sound quality, UN interpreters share suggestions with remote participants so that they can bring their setup into compliance. If remote participants decide not to follow the guidelines and sound quality remains poor, remote participation is not interpreted.

Should sound and video quality suffer on the day of the meeting, the team leader may also decide not to provide interpretation.

Remote participation at the United Nations

For UN meetings, remote participants either join from a meeting room or use a computer.

In the latter case, participants must:

- use a separate microphone, headset with a pivot-mounted flexible microphone or headphones such as Apple EarPods, which are commonly available and have a good built-in microphone. Laptop microphones pick up too much background noise.

- connect their computer using an ethernet cable, which provides better sound quality and a more stable connection than Wi-Fi.

Furthermore, remote participants should:

- only turn on one microphone at a time

- mute their microphones to avoid interference when other participants take the floor

- avoid touching or brushing the microphone to prevent crackling noises

- close doors and windows

- limit background noise

- be careful not to bang Apple EarPods against their shirts.

When participants are sitting in a meeting room, other challenges arise. UN meeting rooms feature an individual, unidirectional microphone for each participant, which helps to screen out background noise. However, a typical videoconference room has a single omnidirectional microphone in the middle of the table. The microphone picks up the sound of rustling papers and cannot balance volume levels for participants sitting farther from the microphone or facing the screen rather than the microphone. A potential mitigation measure would be to place the microphone directly in front of the speaker and request that they avoid extraneous noises, including rustling paper.

When participants are sitting in a meeting room, other challenges arise. UN meeting rooms feature an individual, unidirectional microphone for each participant, which helps to screen out background noise. However, a typical videoconference room has a single omnidirectional microphone in the middle of the table. The microphone picks up the sound of rustling papers and cannot balance volume levels for participants sitting farther from the microphone or facing the screen rather than the microphone. A potential mitigation measure would be to place the microphone directly in front of the speaker and request that they avoid extraneous noises, including rustling paper.

Ceiling microphones are even worse: sound bounces off walls and generates echoes. One potential mitigation measure entails switching off the ceiling microphone and switching on a table microphone. Given the poor quality of ceiling microphones, the United Nations does not provide interpretation unless other microphones are available.

Ceiling microphones are even worse: sound bounces off walls and generates echoes. One potential mitigation measure entails switching off the ceiling microphone and switching on a table microphone. Given the poor quality of ceiling microphones, the United Nations does not provide interpretation unless other microphones are available.

If a room has multiple tabletop microphones, only one should be on at a time. Technicians should be trained to switch off unused tabletop microphones.

If a room has multiple tabletop microphones, only one should be on at a time. Technicians should be trained to switch off unused tabletop microphones.

Various mitigation measures can help improve the setup used by remote participants, including moving to a regular conference room with an internet connection and/or using a unidirectional microphone. However, interpreters face a difficult situation when they argue that the “videoconference room” is not suitable for interpreted videoconferences.

Various compromise solutions have been adopted at the UN:

- For brief conferences (10-15 min), staff try to help remote participants improve sound quality enough to interpret.

- For lengthy videoconferences (over 3 hours), remote participants are only interpreted if they are located in a proper room and use a unidirectional microphone. If sound quality is poor, the team leader may suspend interpretation.

- For mid-length meetings, staff encourage participants to use a unidirectional microphone.

Reducing the number of meeting participants can also decrease extraneous noise and improve sound quality. Sitting back from the table and taking your hands off the table also contribute to better sound.

Finally, video input is key, and is a prerequisite for interpreting remote participants at United Nations meetings. Poor lighting, a poorly placed camera, and a broad camera angle can render a video feed worthless; the speaker should be well lit and centered, and the camera should zoom in so the speaker occupies most of the screen.

In conclusion, initial results are mixed. Five different departments have to be brought together for a sound test, making coordination difficult. At the moment, limited funds have led to a lack of audiovisual technicians. Finally, the whole procedure depends on the involvement of interpreters, and it is up to every team leader to close the gap to ensure progress. As everyone can be a team leader, everyone should take an interest in these new developments and try to become acquainted with the United Nations procedure and guidelines for remote participation.

Conclusion

The remote interpreting seminar concluded with a round table featuring the three keynote speakers and ILO Chief Interpreter Monica Varela Garcia. Participants asked questions about numerous issues, including ethics, rates, relay, research, cloud-based vs. cabled RSI, technical specifications, latency, and stress.

Participants thanked the panelists for their presentations, stressing the importance of continuing professional development and their interest in continuing to explore this cutting-edge topic.

This summary of the AIIC Switzerland Remote Simultaneous Interpreting seminar was prepared by Jessica Ayala, Josh Goldsmith and Sébastien Longhurst.

Check out at all the interesting tweets from our RSI seminar.

Don’t miss the summary of the first RSI workshop.

You will find more information and guidelines in the section “RSI – remote simultaneous interpreting” here.

Picture gallery of the event