THE INTERPRETER AND HISTORY IN THE MAKING

Geneva, October 2019, Evelyn Moggio

Geneva, October 2019, Evelyn Moggio

For the first time, family members of some of the interpreters at the Nuremberg Trials came together to talk about their relatives and the legacy of Nuremberg.

The Nuremberg Trials were among the most significant events of the twentieth century, and the experiences of the pioneering interpreters who worked there had a tremendous impact on their lives. After the trials, some were able to pick up the threads of their previous lives and move on. Others struggled with the trauma of what they had witnessed in and out of the courtroom, and their lives changed forever.

This event, organized by AIIC Switzerland, was a tribute to all the groundbreaking interpreters at Nuremberg who, in extremely difficult conditions, were the first interpreters to practice simultaneous interpreting on such a scale.

The video of this round table will soon be available on DVD – some video highlights can already be viewed at the end of this article.

These personalities, who are no longer with us, came to life through the biographical notes presented by George Drummond and the touching memories shared by their relatives and loved ones in a moving and memorable event.

The audience was a mix of the interpreting community, relatives and friends of the guests, as well as FTI faculty members and students.

Moderator, George Drummond: Nuremberg Exhibition Group Coordinator, member of AIIC Legal Interpreting Committee

Invited guest speakers:

- Miranda Richmond Mouillot, granddaughter of Armand Jacoubovitch, and author of “A Fifty-Year Silence” accompanied by her cousin, Vanessa Fraiberger

- Esther Simha, widow of Eric Simha, accompanied by their sons Alex and André

Helga Priacel, widow of Stefan Priacel - Ursula Gilbert, former wife of Wolfe Frank

- Alexandre Vassiltchikov, son of George Vassiltchikov

- Robert Kaminker, son of Georges Kaminker and

nephew of André Kaminker, accompanied by

his son Roger Kaminker

WELCOME and INTRODUCTION

On behalf of AIIC Switzerland, Rawdha Cammoun-Claveria stressed that the event was the first time family members and loved ones of interpreters who worked at the Nuremberg Trials were coming together to remember them.

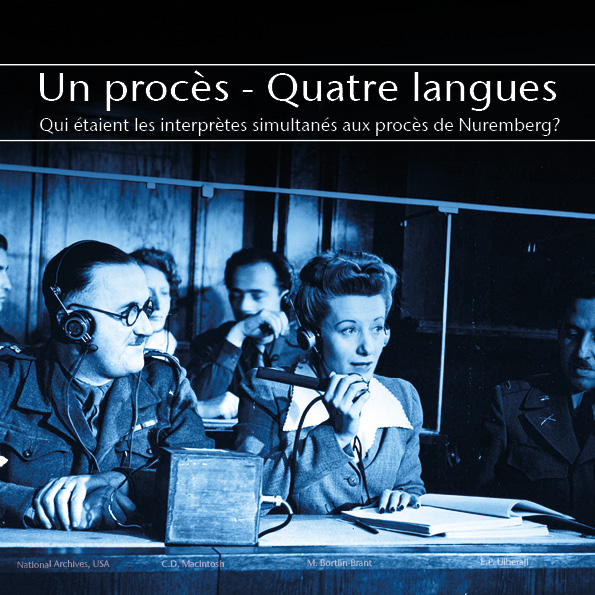

She congratulated Elke Limberger-Katsumi, the curator, on the success of the Nuremberg Exhibition – One trial, four languages – and introduced George Drummond as moderator for the evening.

George Drummond welcomed the guests and the audience, in particular Fausto Gaiba, father of Francesca Gaiba and author of “The Origins of Simultaneous Interpretation: The Nuremberg Trial.”

He also welcomed three former Presidents of AIIC: Monique Ducroux, Gisela Siebourg and Benoît Kremer. We were reminded that on October 1, 1946 the sentences were handed down at the Main Trial in Nuremberg, an historic event that we were celebrating 73 years later to the day in the presence of the relatives of some of those pioneering interpreters.

To set the scene, photographs featured in the exhibition were shown on screen, featuring Room 600 in the Palace of Justice in Nuremberg, where the trials were held, and the interpreters at work in four languages: German, English, Russian and French, The interpreters sat behind open glass panels, sometimes referred to as “the fishbowl”; there were four desks, one per language, with three interpreters at each language desk. They performed an unprecedented task in difficult and stressful conditions.

THE INTERPRETERS

HELGA JÜLICH AND LEO KATZ

Both of German origin, Helga met Leo in Nuremberg when he interviewed her for the language team. After their stay in Nuremberg, they travelled to the United States, where they subsequently married. Dr. Deborah Katz, daughter of Leo and Helga Katz, was interviewed by her daughter, Evelyn Lueker, who sent a video message from San Diego as their contribution to the round table discussion.

The video is very moving. Deborah Katz remembered that her father, Leo Katz, had always endeavored to pass on the idea that Nuremberg was a question of “justice, not revenge” and the lesson learned

from the Nuremberg experience is to show love and compassion for everyone. Throughout the interview, she stressed that they had always been very grateful for what life had given them, and to this end the family’s purpose was to make the world a better place. Ending on a positive note, Deborah explained that, for her father, Nuremberg was plural, as he wrote in his essay “My Nurembergs”: his first Nuremberg was that of persecution, the second that of justice, and the third that of romance, because that was where he met Helga, his future wife.

STEFAN PRIACEL

On March 15, 1946, Stefan Priacel wrote to his wife from Nuremberg: “The work of the interpreter in the proceedings is undoubtedly the most difficult task I have undertaken in my entire life. … The interpreter … performs a true miracle and the most complex of mental processes one can imagine. The nervous tension is considerable … after this performance one feels exhausted, robbed of all substance ….”

Many years later, in his book L’Interprète de Conférence – cet inconnu, he describes his first assignment.

“That day it was the turn of Streicher, the anti-Semitic agitator and editor of “Der Stürmer.” … I interpreted Streicher’s statement that lasted more than an hour … Owing to a phenomenon of de-personalization that I was totally unaware of … I had somehow identified with a person whom everything in me resisted. When Streicher finished I realized that I was an interpreter.”

From 1947 to 1952, Stefan Priacel worked as an interpreter at the United Nations Headquarters in New York. Later, he worked for the Council of Europe in Strasbourg and the European Commission in Brussels and taught at the ESIT in Paris. An obituary in the New York Times described him as “one of the leading conference interpreters on the international circuit.”

Sadly, Helga Priacel could not attend the event for health reasons and we sent her our best wishes for a speedy recovery.

ARMAND JACOUBOVITCH

Armand Jacoubovitch grew up in Strasbourg, the son of a Jewish family. He studied German literature at the university there. In 1942, his parents, Léon and Augustine Jacoubovitch, were deported to Auschwitz, where they were murdered. Armand managed to flee to the south of France, where he worked for the French military until his Jewish origins were discovered. When deportations began there, he and his wife fled under great hardship to Switzerland, where he was detained in several refugee internment camps until he was allowed to train as an interpreter at the School of Interpreting in Geneva.

Armand’s work in Nuremberg had a devastating effect on his personality. After Nuremberg, when family life became impossible, his wife took the children and left for the United States.

Armand continued to work, first as an interpreter at the United Nations in New York and Geneva, and then as a diplomat at the United Nations in Geneva. His colleagues thought highly of him, although he was rather reserved. Stefan Priacel, who remained his friend after the trials, said: Armand “is an outstanding interpreter and a charming colleague, I owe him so much” (“un interprète de tout premier ordre et un camarade charmant auquel je dois beaucoup”).

Many years later, his granddaughter Miranda Richmond Mouillot, puzzled by her family history, resolved to investigate her grandparents’ ordeals. She describes this quest in her book A Fifty-Year Silence.

Miranda explained that she is herself an interpreter and translator, as well as being a writer. The knowledge of languages runs naturally in the family, and thus her grandmother, Anna, who was of Romanian origin, had learned German and French at school.

“The story of my grandfather hinges on what happened in Nuremberg. My grandfather was born in Zurich and immigrated to Strasbourg. He had the cultural background needed to be an interpreter and, besides, the need for interpretation increased as the Austro-Hungarian Empire came to an end and language and nationality came to the forefront. He was a natural candidate for a profession related to languages, since English and French were the languages used in his family.

Also, when he left for Nuremberg, he had had some terrible experiences: he was a refugee at the time of the trials, the family was stateless, he was writing letters to authorities on behalf of his wife and family who had to remain in Switzerland. Because he worked at the trials, he was finally given French nationality. His parents had been deported and he only learned and realized what had happened to them when he watched the films about the concentration camps that were shown in the courtroom. Later, he worked as a volunteer translator for Amnesty International. He left France for Switzerland to campaign against the death penalty.”

George: “Speaking as an interpreter about the atrocities and learning what had happened from viewing the US films on the liberation of concentration camps, did it help to close a chapter in his life, did he ever recover from this?”

Miranda: “No, he never recovered.”

Armand was proud to be working at the Nuremberg Trials; he took pride in his work and in the difficulty of it. The reality of Nuremberg taught him how wrong the death penalty was and he fought against it. It taught him to consider the humanity of the defendants.

He described the experience as a black box into which everything that was said disappeared. For him, interpreting was an act of radical humanity, of equality; he disapproved of the death penalty.

His wife Anna also worked occasionally as an interpreter; she had no foreign accent in any language, and could dissolve into the background with great ease. When they were refugees in a town in France, she interpreted German and French, and thanks to that they were taken off the deportation line.

“Grandfather always said that interpreting could not be done by just anyone. You’ve either got it or you don’t!”

Miranda concluded by repeating her grandfather’s message: “Interpreting is an act of humanity.”

GEORGE VASSILTCHIKOV

George Vassiltchikov went together with Yuri Klebnikov to Nuremberg on January 4, 1946 and interpreted from Russian to English and French until August 12. He reported directly to Colonel Dostert.

Upon leaving Nuremberg, he flew from Paris to New York on August 16, where he worked as an interpreter for the United Nations. He later interpreted for the United Nations in Geneva.

Alexandre Vassiltchikov knew from his father’s accounts about Nuremberg that he was less focused on the technical features of the interpreting process and more interested in the historical experience.

Throughout his life, he accumulated lots of material, but never wrote a book about Nuremberg. However, he edited and published his sister Missie’s diaries, “The Berlin Diaries: 1940–1945”, originally written in English, and later published in French, German and Russian.

Although the Vassiltchikov family had lost their citizenship and were stateless, they maintained a strong family bond. The Vassiltchikov siblings were brought up as members of the imperial aristocracy and were fluent in Russian, French, English, German and later in Italian. They considered the knowledge of languages as one of the tools of their survival.

Wolfe Frank wrote in his notes (edited by Paul Hooley and published in the book Nuremberg’s Voice of Doom): “There was also a phenomenon among us, Prince George Vassiltchikov, an American-born direct descendant of the late Tsar of Russia. I will always remember George for three outstanding qualities: (a) he had three unbelievably beautiful sisters; (b) he became the best Russian–English interpreter at the United Nations; and (c) he suffered from an extremely bad stammer. This, for an interpreter, would appear to be an insurmountable handicap. But George’s stammer disappeared the instant he faced a live microphone. It was an eerie thing to be listening to his linguistic stumbling one second and to hear them replaced by the smoothest possible delivery an instant later.”

Alexandre confirmed that although in normal life he stammered in all his languages, his father considered that when interpreting he was playing a role, so there was no emotional involvement; however, stammering became a severe handicap towards the end of his life.

He remained a close friend of Yuri Klebnikov, of White Russian origin, who later became Chief Interpreter at the UN Headquarters in New York. George Vassiltchikov was a man who had lost both his country and social environment; he retired from the UN to write his book but came back to work for the Inspection Unit and later worked as an interpreter in the United Kingdom and the Soviet Union.

As for his time in Nuremberg, his son pointed out that it was a strange situation for someone who was fiercely anti-communist and anti-Bolshevik to work for Russian prosecutors and judges, given that Andrey Vyshinsky, a representative of the “worst of the Soviet system,” had labeled the Vassiltchikov family “the enemy of the people.”

ERIC SIMHA

Born into a Greek family of Jewish descent, Eric Simha moved to Zurich with his family in 1938, just one day before the November Pogroms (Kristallnacht). They were safe, but Eric’s aunt and uncle were subsequently deported with 13 children from Skopje and later murdered.

In the summer of 1945, Eric finished college and worked at the US consulate using his language skills in German, English and French, where Colonel Dostert met him and offered him work in Nuremberg during the interrogations at the age of 20. Eric later interpreted in the courtroom. He remained there until December 1947.

After Nuremberg, he travelled extensively in Latin America before returning to Europe, where he worked freelance for the Council of Europe in Strasbourg and then became a staff interpreter for the World Health Organization in Geneva. He taught at ETI School of Translation and Interpreting (now FTI), where one of his students remarked, “Eric Simha was one of my best teachers, and the funniest.” He always said to students: “Either you have it or you don´t, I can only help you improve the skills you have”.

Eric’s father was in the tobacco industry and the family lived all over Europe.

Eric met Esther, his wife, during a family trip to Greece. It was love at first sight and they were married three months later.

Esther spoke of her husband as having a great sense of humor, and spoke of the Nuremberg experience with a positive note: Eric was the only interpreter of Greek origin in Nuremberg, where he worked until 1947, as he was an advocate of “learning by doing.” The experience was difficult, but it did not affect Eric’s spirit and good humor, maybe because he was too young, and saw it as an adventure, according to Esther. After 1948, he travelled to Mexico and Colombia, where he was caught up in an uprising. In 1953, he became a staff interpreter. Esther remembered him as a great storyteller, “so much so that he should have been in showbusiness.” They sometimes spoke Ladino at home.

WOLFE HUGH FRANK

Wolfe Hugh Frank was born in Bavaria, the son of an industrialist. He fled to England at the end of the 1930s and later fought against Nazi Germany in the British Army. Because of his excellent linguistic skills, he became an interpreter at Nuremberg. The general consensus among his fellow interpreters was that he was the best interpreter at the trials. He interpreted mainly into English, which he spoke with an upper-class accent. He was responsible (at his own express request) for interpreting the death sentences handed down to the defendants.The Times newspaper dubbed him “the voice of doom.” After the trials, he returned to civilian life, not only working as a freelance interpreter, but also trying his hand at other things.

Ursula Gilbert, a fellow interpreter, met Wolfe in the booth at the European Economic Community in Brussels. She was married to Wolfe Frank from 1975 to 1983 and they had two children. She said that Wolfe rarely mentioned Nuremberg. He maintained a close friendship with Fred Treadwell and Patricia Van Der Elst. She knew he had been Chief Interpreter at Nuremberg, and afterwards he had pursued several lines of work. While working as a journalist, he had established contacts with the BBC and was interviewed by Richard Dimbleby. In 1949, Wolf went back to Germany to speak to ordinary Germans in schools and public places in order to write a series of interviews about the Nazi regime, that were published by the Herald Tribune.

ANDRÉ KAMINKER

Born of a Polish father and Austrian mother, André was brought up in Belgium with his brother Georges, who also became an interpreter.

André gained fame as a legendary consecutive interpreter on the international stage in the era of the League of Nations. He had a phenomenal memory and could accurately interpret extremely long speeches without taking notes.

After the First World War, he worked as a French civil servant in Wiesbaden, where his daughter, later to be known as Simone Signoret, was born. André Kaminker, a journalist before the war, fled to London in June 1940, leaving his family in France where they managed to remain safe. He joined the Free French Forces, did broadcasts on Radio Brazzaville and Martinique and interpreted for General de Gaulle in Africa.

He did not work as a simultaneous interpreter at the Nuremberg Trials. At the preparatory conferences leading to the founding of the United Nations, he headed the “Consecutive Interpreters Team”; he then became a staff interpreter at the United Nations in New York and, subsequently, he was Chief Interpreter at the Council of Europe. He was a one of the founders of AIIC in 1953 and became its first president.

Also Georges Kaminker, as a UN interpreter, was sent together with Charles Le Bosquet, deputy chief Interpreter at UN London, as a UN interpretation team to evaluate the interpretation system in Nürenberg. They concluded it would not be feasible, mainly because it did not give interpreters time to consult, and they took a negative report back to London. Later, Colonel Dostert came to the UN with IBM equipment and demonstrated that it was possible. That system started in Lake Success before moving to the UN headquarters in Manhattan. A few years later, simultaneous interpreting was done in the booth, at the General Assembly and at the Security Council.

Robert Kaminker, who was accompanied by his son Roger, also an interpreter, gave his advice to budding interpreters: “Choose your languages very carefully!”

Video highlights of the round table discussion “Family Memories – Lest we forget”:

A recording of this event is now available on DVD containing two hours of material from this encounter. This volume makes an excellent gift for anyone interested in the history of interpreting and is on sale for CHF 15.00. Please contact the Swiss Regional Bureau at bureau@aiic.ch to purchase it!

Photo gallery – Pictures of this memorable evening

![]() AIIC Switzerland thanks Odeka for sponsoring the simultaneous equipment

AIIC Switzerland thanks Odeka for sponsoring the simultaneous equipment

and the interpreting booths for this event.